Guanxi in the job market,

social stratification, and moral ambiguity

What is Guanxi, and why it can play a determinant role in job search in contemporary China? Does the use of Guanxi bring extra advantages to some job seekers? Is it fair to other competitors? Is Chinese Guanxi corrupting important social values such as justice or integrity, or is it already part of unspoken social norms that everyone knows how to play by? In this essay, exploring Chinese Guanxi around these questions, I want to seek an understanding of Guanxi dynamics in the midst of complicated social relations and values. I remember when I first tried to introduce the idea of Guanxi to a Western friend and explained how in the past it helped my cousin to beat other competitors and get a desirable job in a local commercial bank, his very first response was, “isn’t that corruption?”. “No, they’re different!”, without hesitant, I tried to defend my people. “But how?”. “…Uhh…Guanxi is socially embedded, it’s very complicated!” Well, the moment that feeble answer slipped out I realised how lame and unconvincing it was. A sense of being unjustifiably misunderstood from that conversation then became the motivation for this essay. Not only do I want to adopt a new anthropological lens to look at what really happened on my cousin years ago, but also I hope when I reach the conclusion part, the existence and the logic of Guanxi can start to make some sense to that Western friend in particular, and to everyone who may find this issue slightly interesting.

This essay starts with looking at the concept and characteristics of Chinese Guanxi, pointing out the inherent mutual obligation is an important feature that distinguishes Guanxi from other forms of social bonds, such as blat in Russia or social capital in the West. Then, I will talk about the role of Guanxi in job search, and use two scenarios to showcase how job seekers use Guanxi to obtain desirable jobs on the ground. Next, examining the relationship between Guanxi and other job qualifications such as education background, a connection between the use of Guanxi in the workplace and the phenomenon of increasing social stratification in wider society will be discussed. In the last section, I will talk about moral ambiguity in people’s daily discourse and attitude towards Guanxi practice. Having some conversations with my interlocutors both in the real world and online, what people themselves say about Guanxi will open a new way for us to look at Guanxi dynamics.

In the end, this essay argues that Guanxi practice in job search should not be merely seen as some external strategy that people actively adopt from their tool-box to obtain some desirable jobs for themselves while beating up other competitors. It would be more instrumental if we try to understand Guanxi as an overarching structure that every social being living underneath it has to obey its rules while trying to utilise the system to their own deeds. It may seem that Guanxi gives people of certain social groups some unfair advantages in the ever-competitive job market, but from another perspective, Guanxi is also an inclusive obligatory web that no one can escape from.

♦ What is Guanxi? ♦

What is Chinese Guanxi? Early as in 1994, Mayfair Yang, in her “Gifts, Favors, and Banquets: the art of social relationships in China”, gave out a most instructive definition of Guanxixue, or Guanxi-ology, as “the exchange of gifts, favors, and banquets; the cultivation of personal relationships and networks of mutual dependence; and the manufacturing of obligation and indebtedness (1994:6)”. The first thing worth noticing in her definition is that the practice of Guanxi does not only consist of material forms of exchange such as gift or banquet, but also it can be played in a less explicit form as favour giving and receiving. This means that in some cases the existence of Guanxi relations may not be as easily or clearly identifiable, as oral promises or silent mutual understanding of favour exchange may be hard to grasp or define to outsiders. A second point in the definition is that Guanxi is not a one-time practice that built solely on the exchange of interest, but is something embedded in a person’s deeply-cultivated and closely-bonded social network. A third feature is that rather than a top-down, patron-client type of vertical relationship that favour is passed over from the higher to the lower position in the social hierarchy, Guanxi relationship often emphasises on mutual dependence between members in the network. In other words, the favour-receiver of this time can be, and is expected to be, the favour-giver next time, and the flow of Guanxi practice is flat or horizontal instead of vertical.

A Chinese banquet, a lot of Guanxi is flowing underneath the tablecloth

Why is Guanxi so persistent and significant in Chinese society, and what is specific about it compare to the social capital in the West? To answer this question, a popular opposition between individualism in the West and collectivism in the East may be useful as a starting point, but there is more to look at. From a social relations point of view, we can see all Chinese people as living in a web of social relationships, their “family, kinship networks, work colleagues, neighbours, classmates, friendship circles” are “much closer social structures to individuals than the party-state (Bian, 1994:972)”. But this depiction does not fully explain how close these social structures are and what it means in real life. A functionalist perspective can also shed some light, as Ledeneva, studying the forms of informal practices in socialist countries, suggests that “the primacy of personal relationships acquires a particularly important economic function when goods and services are scarce or difficult to obtain (2008:120).” This explanation links Guanxi to the then widespread material shortage, seeing its practice as an economic strategy people adopted for survival. This theory may be applicable to the pre-reform, socialist period of China, but may not be necessarily true anymore when the opening and reform policy brought in the capitalist economy and the labour market. In the past 30 years, unprecedented freedom on personal choice flooded, but there is very little sign that the old Guanxi practice is losing its vitality.

Probably the most important feature that distinguishes Guanxi from other forms of social bonds is the mutual obligation inherent in the relationship. To understand this, it is crucial to look at the cultural root of Guanxi origin. Deriving from popular Confucianism and the kinship ethics, Guanxi “propagates respect and harmony, imposes a duty of moral and proper reciprocity, and makes a gift an object that serves a ritualized relationship (Ledeneva, 2008:127)”. As realised by any Chinese individuals that they cannot be separated from the surrounding web of social relations, Guanxi dos not just play the role of mutual support and social security, but more importantly, it functions as “a principal moral criterion to evaluate individuals (Bian & Ang, 1997:984)”. In other words, in order to be “a good person” in Chinese society, no matter how great one’s personal achievement can be, it is how much he/she has contributed to the wellbeing of the family, relatives, society and nation that truly counts. The social acceptance and recognition from the community are so essential to the establishment of Chinese personhood, the moral standard which ties people together requires a lot of obligation to fulfil.

♦ Guanxi in Job Search ♦

Guanxi has long played an irreplaceable part in job search in China, although its role and function has changed when China went from the previous state job allocation era to the contemporary job market mode. In the pre-reform period, human labour was considered to be a national resource, and institutional control and assignment of urban jobs left very little space for personal choice (Huang, 2008:470). However, people still developed ways in this rigid system to mobilise their positions and exert some agency through their social network. During this period, Guanxi was, in general, a beneficial practice to ordinary people in “allowing them to satisfy their personal needs and in organizing their own lives (Ledeneva, 2008:141)”. By the time of reform and opening in the 1980s and the further reform period (1993-present), job search in China is for the first time “characterized by the widespread and growing prevalence of labour markets (Huang, 2008:470)”. From the 1980s onward, Guanxi has gradually become more instrumentally oriented as ways “for someone to secure opportunities under party clientelism in the workplace or to break free of bureaucratic boundaries to obtain state redistributive resources (Bian, 2002:107)”.

How do people in practice use Guanxi to grab “good jobs” for themselves today? Extracted from my life experience, a depiction of two scenarios will showcase how Guanxi relations can be utilised as a job-searching strategy. For example, A, aiming at getting a rather desirable job in a local company or a department in the civil service, may use his/her Guanxi network to find an intermediary person who is also a friend of the person in charge of the recruitment. A will be introduced at a banquet to the recruiter, B, by the intermediary, and according to etiquette, A is expected to bring B some decent gifts as showing gratitude to B’s willingness to help. Because A and B did not know each other until brought together by the intermediary, their mutual friend, A’s act of bringing gifts, therefore, can be seen as a material form of instant reciprocity to B’s favour.

Alternatively, if A happen to know C, who works in the place A wants to get employed, and if A and C have been a good Guanxi (e.g. close friends, relatives, etc.) for a long time, things would be much easier for A. A can ask C to help with the job arrangement without immediately paying back to C in forms of extravagant gifts. This is because A and C have known each other long enough and they have helped each other multiple times not only on the job search but various issues. C would understand that this favour he/she has done for A would become an obligation for A to help back in the future, and C knows A understand this condition as well. The former practice between A and B can be seen as a practice of ‘indirect Guanxi’, and the latter practice between A and C as ‘direct Guanxi’, since they are already on each other’s social network.

One thing we should notice is that this classification between direct and indirect Guanxi is by no means an opposite duality. Rather, they are two ends on a Guanxi spectrum, and almost all direct Guanxi between non-relative people starts with the being indirect Guanxi at the beginning of the relationship. Another thing needs clarification is that although this essay mainly focus on the use of Guanxi in the initial phase of job search, it is necessary to realise that in China’s labour market, from the entry into the labor force to later phases of “inter-firm mobility, and reemployment after being laid off”, Guanxi practice can be found in various stages throughout one’s career path (Bian, 2002:107).

♦ Job Search and Social Stratification ♦

To understand the impact Guanxi in the job search has on the wider society, the relationship between Guanxi and other qualifications such as technical skills or education background need a closer look. An interesting old saying in China from Yang’s ethnography goes this way: “Xuehui shulihua, buru youge hao baba. A command of mathematics, physics, and chemistry is not worth as much as having a good father (1994:8)”. It sarcastically points out a hard fact that a strong mastery of scientific knowledge may help you gain access to a good job and a good life, but “having a good father”, which means having someone powerful and influential in the family to take care of everything, can be a shortcut leading to a more successful and easier life. Another more recent but similar example is found in Huang’s ethnography, where his interlocutor Ms Zhang, after herself getting employed by a company through Guanxi network, found that many of her colleagues were also “introduced” by their relatives and friends, “not because they were unqualified or less qualified for the jobs they had obtained but because a great many applicants were, by and large, equally qualified at the entry level (2008:474)”. If the Yang’s ethnography represents an early stage when the transition to labour market was not complete and social stratification was on the way to emerge, then from Huang’s ethnography we can see that today Guanxi still plays a strong role that favours some job seekers than others even when they equally meet the job requirement on skills or education background.

Bringing in the “one of us”, leaving out “the others”

From the early period of material shortage to the contemporary free labour market, Guanxi has gradually evolved into a class-bonded practice. Today Guanxi is widely and almost exclusively used by the people from the middle-class and above as a way to seek and obtain desirable jobs for members in their nuclear family, extended family or friends. In other words, people within their social circle or “people like themselves” are taken in, whereas “the others” are getting excluded. As early as in the 1988 Tianjin Survey, Bian found the phenomenon that job seekers who had close relationships with job-assigning authority at higher levels tended to obtain better jobs, as “respondents whose fathers’ work units had a higher bureaucratic rank were more likely to use guanxi than those whose fathers had a lower rank (1994:987)”. Now thirty years later, in another research Bian collaborated with DiTomaso, they found that the exchange of favours among members of privileged social groups still contributes greatly to their own position within social stratification (2018:9). In this way, by improving outcomes in terms of access of better job opportunities, Guanxi network gives people from middle-class and above more advantages in competition, while constraining those who are in less lucky positions with less social and material resources.

♦ Moral Ambiguity and Guanxi as a Structure ♦

What do people themselves think about the existence and the logic of Guanxi, and how do they talk about it in daily discourse? In my first year in university, one of my roommates was a very able and intelligent girl, and we got along very quickly. Two months into our friendship, when we were walking back to the dormitory one afternoon, she suddenly told me that she was able to study in our program was partly because her uncle had a good friend working in our university, and they transferred her to this program because it was considered better than her original program. That was, for the first time someone admitted to me in person that the position they achieved was thanks to Guanxi, and I can never forget the look of embarrassment on her face, and how quietly she talked. In most of the other encounters with Guanxi discourse, the flow of information is more often like a form of gossip, as people will talk about how they accidentally get to know a third person having used Guanxi to obtain certain jobs, as if they have found someone’s embarrassing secret. When Ledeneva talks about her interlocutors’ reaction to the word “blat”, she describe the existence of blat as an “open secret” that “everybody who is party of a transaction knows about but that no one discusses in a direct way (2011:725)”, and people’s reaction of “knowing smiles” as “a visible sign of sharing and belonging, but are at the same time an expression of ambivalence (2011:721)”. I think there is certain similarity on people’s attitudes between Guanxi and blat, and I suggest the unwillingness to openly talk about Guanxi practices also reveals a degree of shamefulness or sense of wrong-doing felt by people themselves.

It seems that most people are reluctant to open up publicly that certain job opportunities are gained through their Guanxi network, but what if they are confronted more bluntly with regards to the use of Guanxi and its supposed harmful impact on social justice and equality? In Ledeneva’s study on blat and Guanxi, she found that participants in both societies attempt to ‘legitimize’ their use of social resources, and very often their explanation boils down to “the system made me do it (2008:124)”. This type of response also appears repeatedly in my own conversations with Chinese interlocutors, as they will say, “it’s the flaw of the system”, or “everyone else is using Guanxi, if I don’t use mine, I’ll be in disadvantage”. In most of the discussions, people tend to avoid talking about the negative impact of Guanxi, and many of them would justify their use or potential use of Guanxi by emphasising on how themselves are also struggling as the victim of this social norm. One interlocutor in particular tries really hard to convince me to see the positive side of Guanxi, saying “it is a way to help each other to their success”. On the online discussion, I find people are more likely to say what they truly think about Guanxi without being accused of lack of fair-play or morality. One person said “if I failed to get a good job by myself, I’ll use my parents’ Guanxi to get a job in hometown”, and another, “I wish my parents had some strong Guanxi I can rely on, but they don’t.” In other words, from the ambivalent attitude from the interviews, we can tell a recognition of the connection between the use of Guanxi in job search and the increasing social inequality does exist. However, job seekers still think they will, and they think they should, use their Guanxi network to their own deeds whenever it is possible.

At the same time, the people who are asked to offer some help by people from their Guanxi network are also not having an easy time. Due to the obligatory nature of Guanxi, “helping each other” becomes a common practice that is embedded in social relations, which in many situations means some Guanxi requests are extremely difficult to reject. In the earlier scene between the job seeker A and B, their Guanxi practice may seem to be problematic at first, as the gift and banquet involved sounds too monetary and materialistic. However, what makes this exchange of gift and favour between A and B possible is not how valuable the gift itself is, but how the Guanxi network connecting A and B makes B feel compelled to take the gift. In real life examples, it can be that A’s uncle holds an important position in the workplace of B’s wife, or A’s sister is the headmaster of B’s children. Therefore, in many cases when Guanxi is used in job search, we need to be aware that the underlying social network which directs the flow of Guanxi is extremely complicated and influential. To say something such as “B should reject A’s ‘bribe’ out of integrity, or it would be corruption” is neglecting a very basic fact that the people themselves are living under, and constrained by, the power of the overarching Guanxi structure.

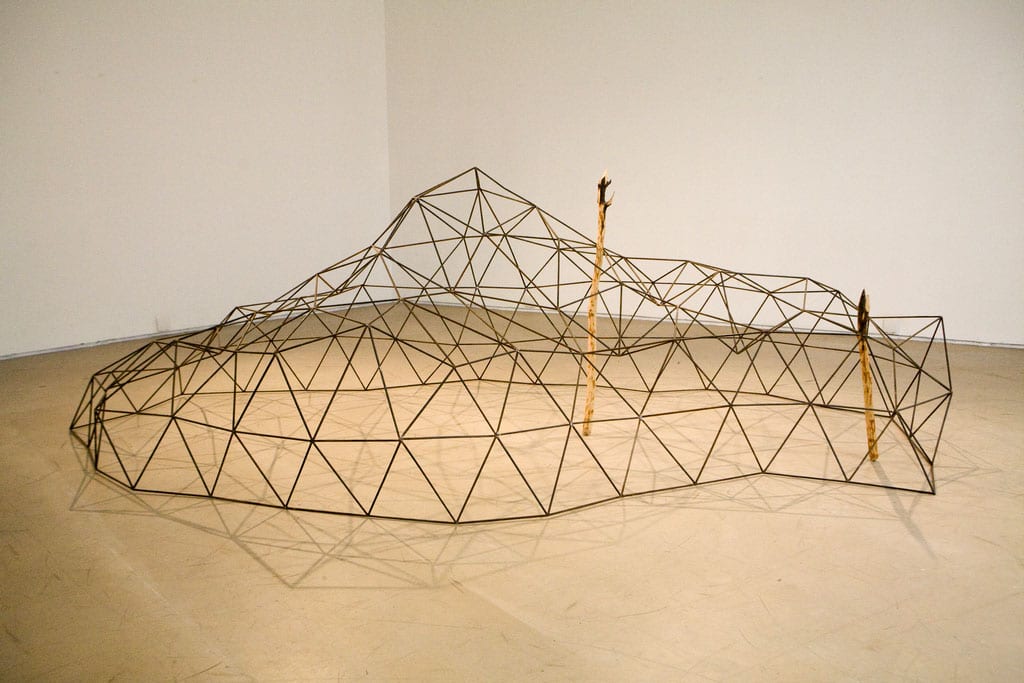

Guanxi structure embedded in complicated social relations

♦ Bibliography ♦

Bian, Y., 1994. Guanxi and the allocation of urban jobs in China. The China Quarterly, (140), p.971.

Bian, Y., 2002. Chinese Social Stratification and Social Mobility. Annual Review of Sociology, 28(1), pp.91–116.

Bian, Y. & Ang, S., 1997. Guanxi Networks and Job Mobility in China and Singapore. Social Forces, 75(3), pp.981–1005.

DiTomaso, N. & Bian, Y., 2018. The Structure of Labor Markets in the US and China: Social Capital and Guanxi. Management and Organization Review, 14(1), pp.5–36.

Ledeneva, A., 2008. Blat and Guanxi : Informal Practices in Russia and China. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 50(1), pp.118–144.

Ledeneva, A., 2009. From Russia with “Blat”: Can Informal Networks Help Modernize Russia? Social Research, 76(1), pp.257–288.

Ledeneva, A., 2011. Open Secrets and Knowing Smiles. East European Politics & Societies, 25(4), pp.720–736.

Xianbi Huang, 2008. Guanxi networks and job searches in China’s emerging labour market: a qualitative investigation. Work, Employment & Society, 22(3), pp.467–484.

Yang, M., 1994. Gifts, Favors, and Banquets: the art of social relationships in China